Beyond the Canopy: The Multi-Scale Climate Impacts of Land Transformation

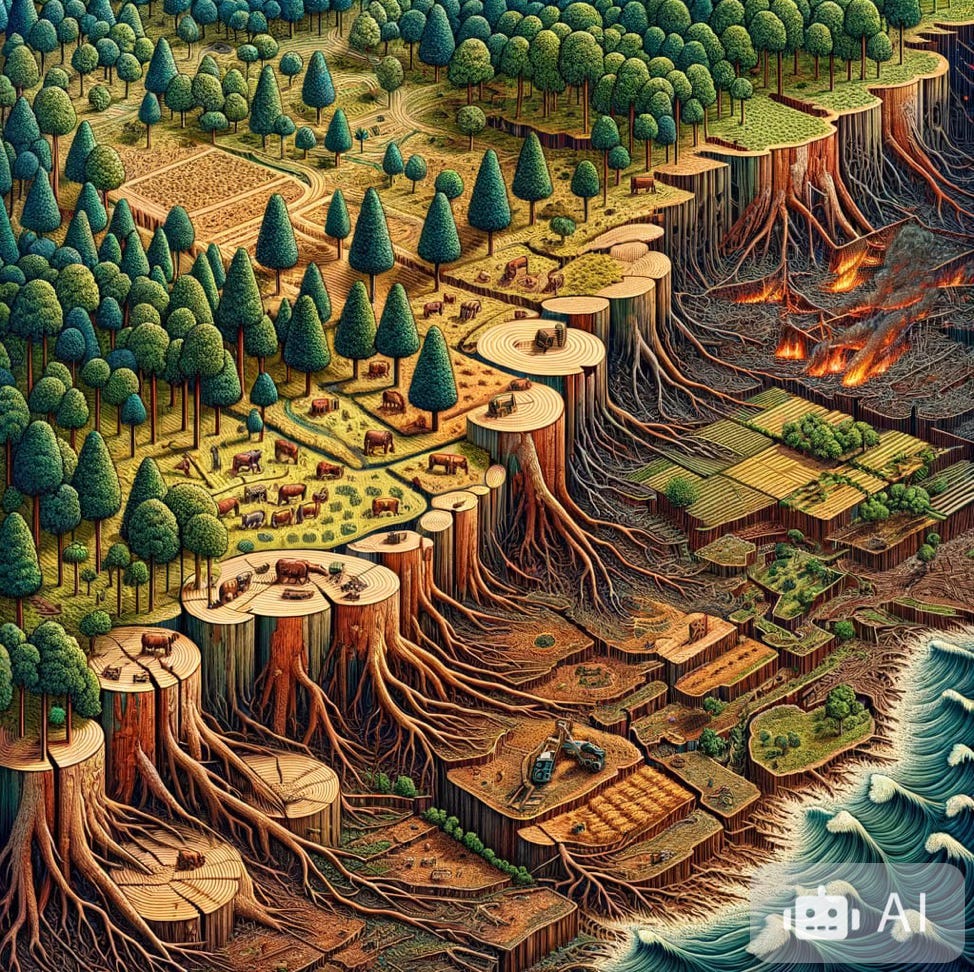

When we change the vegetation across a landscape, we create a cascade of effects with both short term and long terms implications that extend from the very local to the global scale.

Global warming and the climate changes it brings has effects on the landscape, but our management of the land also has huge effects that drive further warming, not just through increased carbon emissions but through a range of other drivers. This does mean however, that if we change some of our land practices, we have a powerful tool to help mitigate and manage the future.

Carbon storage

The most obvious impact of land use change is the amount of carbon, that was previously stored in natural ecosystems and soils, being released to the atmosphere when the land is cleared. This is the typical value that is included in carbon budgets that state that, for example in 2025, projected land use change emissions were 4.1GtCO2. This is only part of the picture though. A mature system such as a forest continues to absorb more carbon and store it for much longer than its agricultural or infrastructural replacement meaning those losses compound each year. The volumes are significant. It's estimated that with a fully intact ecosystem, we could have released 4-6Gt of carbon yearly with little impact, since nature would have been able to absorb it. This natural buffer has however been overwhelmed and is actively being destroyed. Natural carbon sinks are now in decline, despite increased greening in high latitudes as tundra expands into a warming Arctic.

Wildfire impacts

Fire was humanity’s first agricultural tool. As population has grown and the demand for global food production with it, more and more natural forests are being burned for land clearing. In addition wildfires are increasing as global temperatures and droughts increase.

A recent study using high resolution satellite image analysis found that previous estimates of fire emissions were grossly underestimated.1 They found annual emissions 70% higher than previously budgeted at 3.4Gt rather than just 2Gt of carbon.

Apart from the obvious initial emission of carbon to the atmosphere, there are many other impacts.

Soot fall out in the Arctic from tundra fires increases the heat absorption of the ice, melting it faster and reflecting less sunlight back into space. Aerosol emissions can change weather patterns, even effecting photosynthesis rates for hundreds of miles downwind of the fire.

The longer term impacts of fire occur during recovery which can last from months for grasslands to years for forests, reducing their capacity as climate moderators and CO2 sinks.

Deforestation

A tropical rainforest such as the Amazon, or those in Indonesia and the Congo Basin, are sensitive to CO2 levels and associated temperature changes. A recent study of the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) found that vegetation was generally able to adapt to the geologically rapid temperature increase (5-6ºC in 5,000 years, at least 100x slower than today’s warming rate) until approximately 4ºC of temperature rise was reached.2 After that point, some vegetation sinking function of carbon was lost and it took 70-200 thousand years to recover.

As well as acting as carbon sinks, absorbing a proportion of our emissions, rainforests also move moisture around and crucially, create clouds which reflect sunlight. If we lose a forest, we lose reflectivity, meaning the Earth’s Energy Imbalance (EEI) goes up. This pushes up the temperature by more than just the emitted greenhouse gases would have done on their own.

The Amazon rainforest is a known and well studied tipping element with an estimated rise of 4-5ºC required to tip it from a forest to a savanna. However when human deforestation and degradation are included, that figure drops significantly. With 20-25% deforestation the tipping temperature drops to 1.5-2ºC. Today deforestation has exceeded 17% and temperatures are 1.5ºC above pre-industrial.

The human action of deforestation and degradation has lowered the tipping point bringing a critical step in containing atmospheric CO2 to a lower temperature and forward by over 100 years, even if we kept current fossil fuel burning rates. At the same time cloud reduction has steadily increased the EEI and pushed up the temperature, not just locally but globally.

Soil changes

Mechanical land clearing, from the axe to the bulldozer, is the second major impact on the land. Soils are impacted in many ways, mainly through soil moisture changes, topsoil loss, compaction and exposure leading to degradation. On flat lands, changes range from salinity issues to water stress and aridification.

Soil salinity is naturally occurring but land management practices can increase the salt content of the soil, degrading it and inhibiting crop production.3 This can occur through irrigation with brackish or saline water, rising water tables due to poor land and water management, surface or sub-surface sea water intrusion into coastal aquifers as a result of rising sea levels or over-exploitation of the fresh underground waters, and overuse of fertilisers. Degraded soils carry less carbon and are less productive, leading to further demand for new growing areas. Millions of hectares in Australia alone are affected by this phenomena but globally they are seen to increase in many areas as the climate changes.

Water content of soils is a major concern. Land clearing dries the top layers of soil and increases water run-off when there is rain. This not only produces problems of flooding downstream, but reduces infiltration and therefore the water available for crops and vegetation on the cleared land. Cropping and grazing also reduce soil organic matter, further lowering its water holding capacity. 1 gram of soil carbon can hold 8 grams of water, therefore if you lower the carbon content, you dramatically lower the water holding ability.

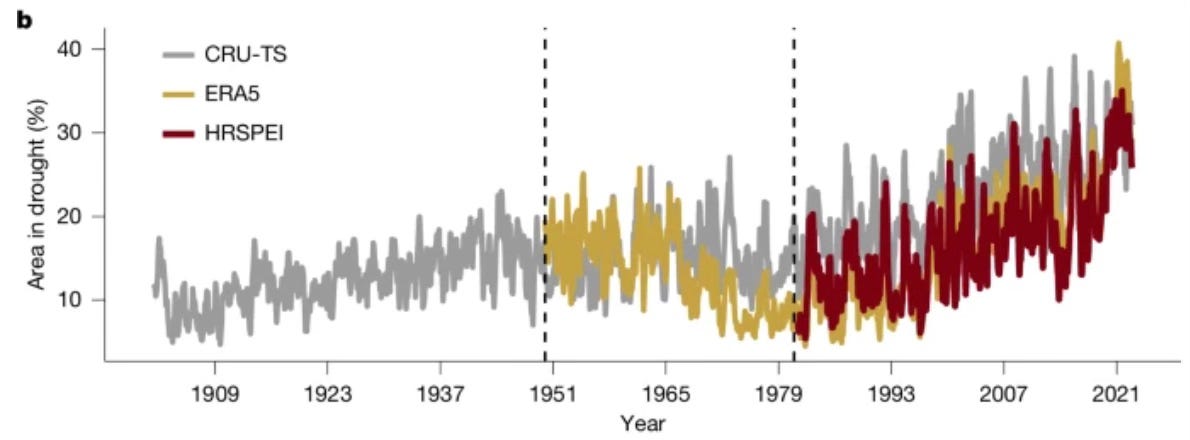

This is accumulative and results in soil moisture deficits. The land then lacks the ability to sustain productivity during prolonged dry periods. This coupled with the reduction in the ability to create cloud and rain through biological enhancement is leading to an increase in drought severity globally. So, although annual rainfall averages over many areas have not changed much, their impact has changed greatly. The vapour pressure differential from the drier regional impact of land clearing has multiple cascading effects which will only get worse with increased warming. A recent study found that the observed global area in drought between 2018 and 2022 was 74% higher than the 1981-2017 average at 27% of the global land surface.4

Biotic pump

Whilst ocean derived clouds deliver rainfall far inland, they are intermittent and often heavy, vegetation moves moisture across the land in a more continuous and far reaching way, often reaching further than ocean rain could do so. Plants do this by drawing water from the soils through their roots then transpiring it from their leaves and needles as part of the photosynthesis process. Stomata on the underside of the leaves open and close to control the flow. Cumulatively the volumes are huge, driving local, regional and global weather patterns and enabling great regions of the Earth to remain lush despite their distance from the oceans.

A mature tree in a tropical rainforest can pump 1,000 litres of water a day into the atmosphere. Often they have leaf areas 10 times greater than their land area, so can transpire far greater volumes of water, for longer, than evaporation from equivalent water surfaces. This moisture combines to form clouds that later rain out, carrying the water deeper inland. The creation of the clouds also creates a low pressure area above the forest that draws moist water in from the sea, ensuring the constant supply of moisture. If this chain is broken, it has serious impacts on water availability downstream. The balance between oceanic and terrestrial rain can be delicate and sensitive to disruption caused by land use changes as it competes with salt spray in the ocean which has a warm rain collision–coalescence temperature generally well above zero. Collision-coalescence temperature is very important as it can control where it will rain first and therefore provide convective cooling through atmospheric mixing.5

It has even been suggested that Australia had much more forest cover before the first humans arrived in the north. Their burning from the coasts inland especially in the northern forests, cut off the biotic pump that then starved the rest of the continent of moisture, helping to creat the drylands that exist today. For an excellent discussion into the Biotic Pump, we can recommend this conversation between Nate Hagens and Anastassia Makerieva:

The biotic pump does not just serve the local forest, the waters travel thousands of miles inland. In fact a recent study showed that crop production in 155 counties rely on forests in other nations for up to 40% of their rainfall.6

As an ecosystem dries it behave very differently. High temperatures and seasonal water stress accelerate microbial activity, leading to rapid turnover of organic matter. Because decomposition outpaces inputs under these conditions, soils in savannahs, dry forests, and semi-arid rangelands naturally hold less carbon. When land is converted to cropland or subjected to intensive grazing, this delicate balance is pushed even further toward carbon loss.7 Practices such as slash-and-burn clearing, repeated tillage, and the replacement of deep-rooted vegetation with short-lived annual crops reduce carbon inputs while exposing stored carbon to oxidation. Over time, the soil’s physical structure changes as well, aggregates that once protected organic matter break apart, making carbon more vulnerable to microbial decomposition and vastly increasing erosion by water and by wind.

When moisture transport is reduced, it has heating effects downwind which can effect huge regions. An historical study of the great American dust bowl found that the teleconnections from the heating over the Great Plains themselves from the drought and land use conditions are necessary to account for the unprecedented heat extremes over large areas of the Northern Hemisphere in the 1930s that have only recently been approached or exceeded.8

History is now repeating itself but on a global scale. A recent UN report showed that 77% of land has become drier in recent decades, and drylands now cover 40.6% of the Earth’s land surface. The number of people living in drylands has doubled to 2.3 billion, and this may reach 5 billion by 2100.

Soil leaching

Exposed soils which were once held in place by deep roots are much more prone to rain runoff and this leaches the organic matter from the soil, carrying it to streams, rivers and eventually the oceans. Vast amounts of carbon are transported this way naturally, but land use change has increased this carbon loss dramatically. One study suggests this accounts for up to 1Gt of soil carbon loss annually, up to 60% of which ends up in the atmosphere. This is not included in soil outgassing calculations.9

This run-off also changes the chemistry of river systems, effecting their habitability for many species.

Vegetation aerosols and cloud feedbacks

Perhaps one of the most important effects of vegetation change is the loss of natural organic aerosol production and their replacement with dust and smoke that is changing the cloud cover of the globe. Through deforestation we are creating vast differences in our atmospheric concentrations of fine particles which effect condensation, coalescence and ice nucleation which effect not only the amount of rain but also rain availability temperature points.

Walter Jehne, a leading soil scientist in Australia, points to the stomata microbial release as being a great source of high temperature hygroscopic precipitation nuclei.10 He states “Natural precipitation nuclei; primarily ice crystals, specific salts and certain highly hygroscopic bacteria can do this and dominate the natural nucleation and precipitation of rain in warmer, inland and forested regions”.

He goes on to state that “vast quantities of water vapor are transpired or evaporated into the air daily. Up to 50,000 ppmv of water may be in the air either as water vapour or liquid micro-droplets at any one time. The quantity and length of time this water is retained in the air depends on the level of micro-nuclei in that air and their production via natural aerosols or by our eroded dust, pollutants or particulate emissions. As the haze micro-droplets are far too small to settle under gravity and often have electrostatic charges that prevent them from coalescing they often form extensive, persistent humid hazes and pollutant smogs. These hazes and smogs warm the atmosphere by absorbing solar radiation while in their liquid phase causing them to evaporate and further warm the air by absorbing re-radiated infra red heat while in their gaseous phase. While the latter is the dominant water vapour component of the natural and enhanced greenhouse effect both of these heating processes contribute to the recent abnormal warming and increased climate extremes. These persistent humid hazes have also contributed to the aridification of large regions via humid droughts. These are caused by the inability of the charged micro droplets to coalesce and then precipitate from the air and result in the persistent high humidity but reduced rainfalls of up to 30% recorded in many regions.”

“Humans have greatly increased the addition of these micro-nuclei to the air; via the 3-5 billion tonnes of fine dust aerosols that are added annually due to our land degradation and desertification.”

The decline in latent heat flux further amplifies nocturnal warming, since longwave radiation emitted from more exposed dry surfaces is increasingly absorbed and re‑radiated by dust and pollution haze rather than being lost to space through a clear atmosphere.

The Earth is also dimming, primarily due to cloud loss and changes in cloud brightness. This has a direct effect on warming since less short wave radiation from the sun is reflect back out into space. This increases the Earth’s Energy Imbalance meaning that more and more energy is accumulated. This is driving the current acceleration in warming.

There are other reasons for this cloud reduction, from a reduction in shipping fuel aerosol emissions, natural warming feedbacks and variations between the northern and southern hemispheres, but important reductions in biologically brightened clouds through declining natural plant produced aerosols and their replacement with smoke, soot and fine dust particles are a major factor and an important additional climate impact of land use change.1112

To find out more about how soils can be rehabilitated, we can recommend the following webinar presentation from Vertebra Ecological Engineering. The whole video is worth watching, but the piece we point you to starts at 53 minutes in.

Beef & dairy farming

Ruminant livestock including cattle, sheep, goats and buffalo account for 51% of global mammal biomass. Humans account for 36% and wild mammals have been reduced to just 5% of the total.13 What’s more, ruminant livestock is increasing by 0.5 million individuals every week! Ruminants burp methane as they digest their food, these emissions account for roughly half of all agricultural greenhouse gas emissions.

This is not a short term emission though, so the normal way of assuming methane is a short lived gas is less relevant. This is a growing constant within our global society. Rather then spreading its impact over 20 years, this is now a constant climate driver having a real impact on the EEI and therefore the global warming rate.

Agricultural methane emissions total approximately 170 million tonnes a year (Global Methane Tracker 2025). As a constant we can use the in-air global warming potential of 120xCO2 for its action. Agricultural methane is then the equivalent of an extra 20.4Gt of CO2 each year. Using a realistic half life, that becomes the equivalent of 15.3ppm of additional CO2 being held constantly in the atmosphere. The effect of this today is that the beef and dairy industry is responsible for between 0.15º to 0.25ºC of current global temperatures.

In addition much of today’s farming land is used to produce fodder for the cattle industry. Moving away from this food source would have a dramatic effect on land availability and therefore deforestation, allowing many more regenerative approaches to thrive and counter all the effects described above.

Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity

Throughout geological time, global temperatures have been set by the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere. Scientists use a constant called Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity (ECS) to describe this relationship. If you double CO2, temperatures will rise by a set amount once all the feedbacks and natural systems have settled out. The relationship is logarithmic so you get the same increase in temperature rising from 200 to 400ppm as you do rising from 1,000 to 2,000ppm. The IPCC puts this value in range between 2.5º and 5ºC of warming for a doubling of CO2, but recent studies suggest 4.5ºC as the most likely value.

Humanity is not just pumping CO2 into the atmosphere, it is also tampering with many other natural systems that affect carbon storage, cloud physics and ecosystems. These changes, of which land use change is the greatest, are driving ECS upwards from what would occur naturally if say a volcano had created our equivalent emissions.

This gives us two intertwined duties in restoring the planet to a healthy balance, decarbonisation including carbon removal, and repair of the landscape and ecosystems to support natural processes rather than destroy them.

Conclusions

Whilst the atmospheric concentration of CO2 is the primary driver of our eventual temperature landing through the equilibrium climate sensitivity value, the true situation is more complex and nuanced. The current rate of change in concentration and temperature rise is totally unprecedented in geological time, in addition there are other drivers which we are affecting. In doing so, we are adding multipliers to the ECS which will lead to higher temperatures than many of the models or even paleoclimate studies suggest.

This also means that there are two tools available to us to reduce the temperature rise, its rate and the impacts they bring.

Decarbonisation and eventual carbon removal are obviously crucial. But improved land use practices and ocean husbandry are equally valuable, especially in the near human relevant timescale and in the avoidance of tipping points. The vertical connectivity of the biosphere from the soils and roots to the cloud seeds are critical to maintain and support. The connections keep us cool, regulate weather, manage carbon storage and feed our crops.

Halting deforestation and degradation and replacing it with reforestation and protection provide outsized benefits though more stable cloud and rain propagation, albedo correction and with it lower EEI and ECS multiplication.

Reducing beef and dairy consumption also has good potential for slowing warming and reducing the ECS. It would also free up huge amounts of land, currently farmed for animal food, to be used for human food and re-wilding.

Returning the planet to a safe landing is not just about decarbonisation, though that is a key part. It is also imperative that we treat the soils, oceans, forests and other ecosystems sustainably. If we carry on as we are, we are guaranteeing the worst of outcomes. If we behave more responsibly, we improve the prospects of the approaching decades. This is not just for our grandchildren or children, its for all us alive today too.

van der Werf, G.R., Randerson, J.T., van Wees, D. et al. Landscape fire emissions from the 5th version of the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED5). Sci Data 12, 1870 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06127-w

Rogger, J., Korasidis, V.A., Bowen, G.J. et al. Loss of vegetation functions during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. Nat Commun 16, 11369 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66390-8

Hassani, A., Azapagic, A. & Shokri, N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21st century. Nat Commun 12, 6663 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26907-3

Gebrechorkos, S.H., Sheffield, J., Vicente-Serrano, S.M. et al. Warming accelerates global drought severity. Nature 642, 628–635 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09047-2

Jiang, Y., Burney, J.A. Crop water origins and hydroclimate vulnerability of global croplands. Nat Sustain 8, 1491–1504 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01662-1

Pranindita, A., Teuling, A.J., Fetzer, I. et al. Forests support global crop supply through atmospheric moisture transport. Nat Water 3, 1243–1255 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00518-4

Wang, H., Ciais, P., Yang, H. et al. Land use-induced soil carbon loss in the dry tropics nearly offsets gains in northern lands. Nat Commun 16, 10008 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64929-3

Meehl, G.A., Teng, H., Rosenbloom, N. et al. How the Great Plains Dust Bowl drought spread heat extremes around the Northern Hemisphere. Sci Rep 12, 17380 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22262-5

Yuanyuan Huang et al. ,Size, distribution, and vulnerability of the global soil inorganic carbon.Science384,233-239(2024).DOI:10.1126/science.adi7918

Yli-Juuti, T., Mielonen, T., Heikkinen, L. et al. Significance of the organic aerosol driven climate feedback in the boreal area. Nat Commun 12, 5637 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25850-7

Mingxu Liu, Hitoshi Matsui, Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation Regulates Cloud Condensation Nuclei in the Global Remote Troposphere, Geophysical Research Letters Vol 49, Issue 18, 2022 https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL100543

Am glad you mentioned biogenic aerosols. A cooling mechanism lost as the trees get razed.

Really strong breakdown of the biotic pump concept here. The part about forests transpiring 1,000 liters per day is wild and something most climate discussions completley miss when they fixate on carbon alone. I remmeber reading about Australia's historical forest loss and never connected it to the dry interior conditions, but the chain of cause and effect makes total sense once spelled out like this. Glad someone's connecting these dots.